Act 1

May 26, 2021, at three in the morning on a stormy night, lightning struck and I was lying awake in bed. Thunder boomed and my mind was alight with a new story. I had just started writing a Romcom, but this new idea was beyond alluring. It was of adventures and action, love and betrayal, and I was convinced it would be something grand.

A simple scene came to mind; two men sitting in a train car, one white, the other brown, and they were in love, perhaps husbands. They didn’t have clear faces, but I had an idea of who they were. They were discussing their next big hit—a golden heart—while gazing out the window. There was a gold-tinted elegance to the scene, to the way they interacted, and I was mesmerized.

The next day, before school started, I created a Google Doc jotting down all my ideas for the story. The first thing that always comes to me are the characters, so I made an extensive bullet point list for what would become Montoya and Rose.

The fundamental ideas haven’t changed since May: The Misadventures of Montoya and Rose or “TMOMAR” takes place in the 1920s where an archeologist, Montoya, and a scammer, Richard Rose, hunt down mystical artifacts. Reminiscent of Indiana Jones and The Mummy TMOMAR is a story meant to be brimming with action, adventure, and magic.

I never had a particular reason for making Montoya Indian (hailing from India), that is simply how I envisioned him. Much like how I always envisioned Rose as white and redheaded. I wanted Montoya to be the main character because I liked how composed, intelligent, and well-researched he is. I also noted how in many of the inspirations listed above, many of them don’t feature a POC as the main character, and I just… wanted to. Not because I thought I would be some sort of a savior, but because I like how Montoya is, I want him as the lead, and I don’t see it all that often.

The development for the story continued on unbothered for some time. I submitted the first chapter for a creative writing class in April (I got an 80 on it), and went to work.

Then, I discovered a YouTube show that would alter my perspective and inadvertently lead to the death of TMOMAR.

Act 2

“Book CommuniTEA” is a YouTube series created by Jess Owens discussing the “goings on in the bookish community”. Owens goes into depth about the drama and discussions floating around on bookish Twitter and gives her opinions on the matter.

I fell into the series because the videos are long enough for me to listen to while I got ready for school, and because I enjoyed (and still do enjoy) Owens’ wit and perspective on the drama. I watched those videos every day and I noticed a shift in how I was thinking.

Before I continue on, while Book CommuniTEA was very influential, I am in no way blaming Owens for what happened, nor do I think it’s her fault. I was, and still am, an easily influenced teenager, and it could have been any kind of series that led me to think in the manner in which I did.

Through Book CommuniTEA, I was beginning to deeply think about the perspectives of the POV voices on Twitter about representation in literature. I was introduced to the idea that a white (cis-gendered, straight, able-bodied, etc) writer should “stay in their lane” and “write what they know”. To be clear, these are not necessarily the opinions of Owens, rather, these were the opinions of nameless Twitter users that she was reading off of.

From there I learned more about the #ownvoices movement in traditional publishing; the idea that more stories about minorities should be published by people in that minority group. Since its origin in 2015, the movement has come under harsh criticism for not holding up to scrutiny. If you want to learn more about this subject matter, I recommend watching Rachel Writes’ video “Writing Diversely & the problem with ‘staying in your lane’”.

At this point, TMOMAR was trucking along, and I started doing research for it (up until that point it was primarily character and plot building). I learned about the deep-rooted discrimination against Asian people by the United States, and I was in shock. I was not aware that they were not allowed to be naturalized citizens until the 1960’s, and less so about the numerous bans against them. My American schooling never taught me about the dehumanization of Asian people in my own country. I found out about it from a Young Adult book, not a textbook. This set me off, but it also filled me with guilt.

How was I so unaware of this? I felt cheated by my school system, but I felt awful about myself for not knowing such a dark and massive part about history. For what felt like for the first time in my life, I was made painfully aware of my privilege as a white person; I could easily live my life not knowing because American society has constructed itself in such a way where I didn’t need to know.

This altered not only my worldview but how I saw TMOMAR. I thought, how can I write a story set in the 1920s and not talk about this? Montoya would constantly be faced with horrible, blatant racism because he’s Indian. While I was aware of the racism of the 20s, and while I assumed that Montoya would be treated worse than his white counterparts, this was more specific, it was more informed.

This is where I started thinking that I needed to write a trauma story. This is where everything went horribly wrong. From my (limited) knowledge of a sensitive topic, I assumed that I needed to hyperfocus on that sensitive topic in order to tell the story I wanted to tell. TMOMAR shifted from being an adventure story—something well within “my lane” to write—into a story I had (and still don’t have) the qualifications to write.

Why did I feel I needed to change TMOMAR?

I didn’t want to write a novel set in the past and ignore the issues that the 20s had. I wanted to stay true to the era and not glorify it.

But there’s magic in that world. Naturally, I was very closely adhering to reality.

It was a vain attempt to do what my predecessors in this genre (to my knowledge at the time) didn’t do. It was to be sensitive to Asian and Indian people who lived in the United States at that time.

Then the misguided puzzle pieces were forced together.

Act 3

I was beginning to “write outside my lane”.

If TMOMAR is set in the 1920s, it follows a POC protagonist, and because of that I have to focus on the racism and discrimination that he would face, but I’m white, therefore, I cannot write that story.

“Part of the issue for me was not seeing Montoya beyond his race.” I said in a video I posted to Instagram on this subject.

All the voices and opinions of strangers swirled around in my head, and I took the bits and pieces of their narrative and constructed one of my own. I was terrified to “write outside my lane” and risk hurting people. But no one in my actual life told me to quit. No one that knew me supported these ideas. Everyone I talked to about this was kind and supportive, and they offered fantastic advice.

And that’s where the majority of fear stemmed: not wanting to hurt others.

One of the things talked about in Book CommuniTEA is how well-intentioned white (among other things) authors missed the mark in trying to tell a diverse story. I thought that it would be better for me to not write the story at all than to miss the mark, hurt others, and be a “bad” person. I felt I had to give up the story because I was afraid of the research necessary in order to tell that version of TMOMAR well. But even then, I had a defeatist attitude.

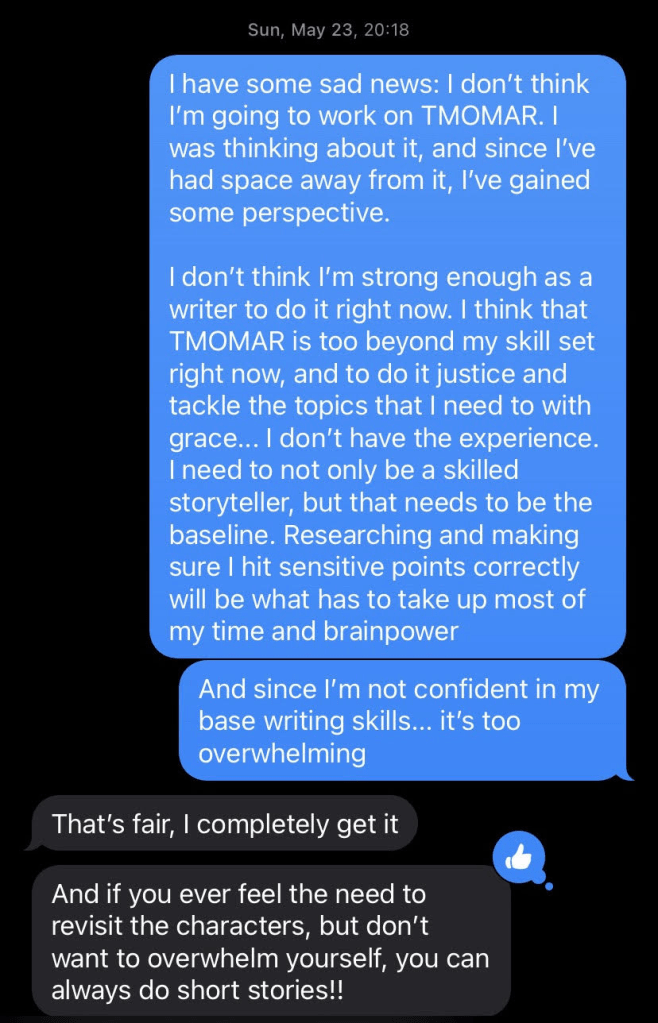

I decided the best thing for me to do was to quit.

On social media and with my friends I didn’t dive into the racial component of this decision because I didn’t feel comfortable talking about it. Plus, the fact that I was terrified of the mountain of research that needed to be done and the general mounting fear of the project were enough reasons for me to quit.

I fell into a mourning period. At that point, I had spent three months of my life growing attached to my characters, their story, and all the little things associated with them. When I caught myself listening to a song and thinking that’s something Montoya would enjoy I would mentally slap myself on the wrist.

Around that time I also fell into my worst writing slump to date—but there were many, many factors leading to that. I felt worthless in my writing and by extension, myself.

About a month later, I was tired of listening to the same sort of music I had been listening to and decided to poke around on the abandoned TMOMAR playlist. In an instant, all the ideas, the hope, the adoration for The Misadventures of Montoya and Rose flashed before me. All of the reasons I started writing that story to begin with. All the reasons I fell in love with it.

Because of the time I spent away from it, I realized that what I thought about wasn’t making it realistic, it was putting the ‘fiction’ in ‘historical fiction’. TMOMAR didn’t need to be focused on the horrible bits of the 20s because that’s not what it was about. There is enough room for me to understand and acknowledge the racism of the 1920s while not fixating on it.

This is what my friends were telling me all along.

I treated TMOMAR like some ground-breaking literary novel about the nuances of racism and placed that weight onto my weak shoulders. And I collapsed.

Epilogue

TMOMAR has not been easy to write, but I have loved each and every moment of it. I have a lot of research ahead of me, and I always will, but I’ve been chipping away at it. When the first book is readable, I’ll hire sensitivity readers to help me fill in the gaps and make sure the book isn’t being offensive with its portrayal of Montoya and other POC characters. I’ll make sure to respectfully ask people questions. I’ll do all that I can so that TMOMAR can properly convey what it’s supposed to be: an adventure story with larger-than-life characters and magic.

To a certain extent, Past Jay was correct in not wanting to write outside his lane. I think in some ways, it prevented a catastrophe of a book, and in others, it stifled creativity. “Write in your lane” and the ideas behind it are so complex and nuanced that I can’t cover it in this post.

It has been a long journey to come where I am now, and I don’t see it ending any time soon. However, I am passionate about my story and my characters and I’m willing to learn. And right now, that’s all I can hope to do.

One reply on ““Write in Your Lane” Made Me Quit My Series”

[…] have a whole article detailing my experience with “write in your lane”, and in short, it made me (temporarily) quit a project I adore. In modern times, this advice is […]

LikeLike